Who among us has not envisioned a more perfect society? One that will be realizable if only everyone (masses and elites alike) could be convinced to adopt the one true path? One realizable if all of us were to follow the inspired leaders who promise perfect happiness!

A few science fiction authors have written to advance their views as to the perfect society (ahem, Ecotopia, cough cough). But it has been as common, or perhaps more common, for authors to imagine either flawed utopias (The Dispossessed) or dwell on the miseries that follow mistaken idealism.

Here are five books about idealistic pursuits that failed.

The Mercenary by Jerry Pournelle (1977)

Fearing nuclear war, the United States of America and the Soviet Union formed the CoDominium, dividing Earth between them. This cynical power-sharing arrangement has thus far succeeded in its two goals: world peace and entrenched power for the American Unity Party and the Russian Communist Party.

Of all the American parties, only the Unity Party is willing to make the compromises necessary to keep the CoDominium functioning. The Unity Party is threatened in the polls by the pugnacious Patriot Party and the idealistic Freedom Party. If the voters are too irresponsible to vote Unity, the only choice for continued world peace, then it is the duty of men like the Honorable John Rogers Grant to protect voters from their own terrible judgement. That this will keep Grant in office is but a trifling side effect.

I apologize to modern readers for whom the idea of an American political party making common cause with the Russians in exchange for short-term political is absurd. It was the Cold War! There were lots of odd ideas floating around. In the Unity Party’s defense, their belief that they’re America’s only bulwark against nuclear war does prove correct… unfortunately for most of the inhabitants of the Northern hemisphere.

In the Hands of Glory by Phyllis Eisenstein (1981)

When the unworkably vast Stellar Federation bowed to reality and dissolved itself, the officers of the Stellar Patrol found themselves suddenly unemployed. This was unacceptable to General Bohannon of the 36th Tactical Strike Force. His force easily conquers the agrarian world of Amphora—just the first step in Bohannon’s grand plan for the future of the galaxy.

Eighty years later, Lt. Dia Catlin has been loyally playing her part in achieving the vision of the long-dead Bohannon. Captured by Amphoran rebels still not reconciled to Patrol rule, Dia’s eventual rescue turns her into a Patrol hero. This in turn puts Dia in a position to discover the undisclosed portion of Bohannon’s glorious plan… an “Are we the baddies?” revelation sufficiently alarming to compel Dia to switch sides.

Points to Bohannon for setting in motion a social movement still active long after his death. However, as characters in the novel observe, his grand scheme is basically a less workable version of the Federation, which, as was previous established, never managed to successfully administer a realm on a galactic scale.

Shadows of the Short Days by Alexander Dan Vilhjálmsson (2014)

Garún is determined to see the rise of a just, egalitarian society in Kalmar-occupied Reykjavík. Garún works tirelessly in the cause of reform despite the considerable personal risk involved. Garún is one of the half-human and despised huldufólk; in the eyes of the Kalmar Commonwealth, Garún and her people have no rights that need to be respected. Should she be detained by the authorities, she can expect punishment that will be even more dire than the dismal fates meted out to fully human dissidents.

Garún’s ex-boyfriend Sæmundur has a cause of his own. Sæmundur is determined to master the forbidden esoteric secrets of galdur, magic by another name. In Sæmundur’s hands, galdur could transform Garún’s revolutionary quest. Should Sæmundur succeed in his aims—and nothing seems sufficient to deter him—nobody will call Sæmundur “Sæmundur the Mad” again. Quite possibly because there will be nobody left alive in Reykjavík to do so.

Garún is a legitimately inspirational figure. Alas, her ex, Sæmundur the Mad, is the sort of deranged researcher who gives vainglorious tampering in domains that have been forbidden to humans for good reason a bad name. Not only is he determined to undermine reality itself, the means by which he funds his research are socially irresponsible at best.

These Fragile Graces, This Fugitive Heart by Izzy Wasserstein (2023)

Mid-21st century Americans enjoy the full benefits of climate change and corporate domination without the distraction of functioning state or federal governments. Kay refused to serve the oligarchs. Kay also refused to simply starve. Instead, she founded a commune. Under Kay’s leadership, the commune has survived while remaining loyal to its founding principles… despite considerable pressure to compromise.

Kay’s death seems to be suicide. Kay’s ex-girlfriend Dora is certain that Kay was murdered. Worse yet, Dora believes that the killer had to be a member of the commune. Dora is not quite correct about what’s going on. The situation is actually much worse than Dora fears.

This novella is admittedly something of an outlier to my theme, in that the idealists aren’t the problem. The pragmatists are. Further, Kay has somehow managed to keep the commune on mission without becoming some sort of cult leader. Due to the focus of the story, we don’t see how she managed that trick. There has to be more to it than sincerity and hard work…

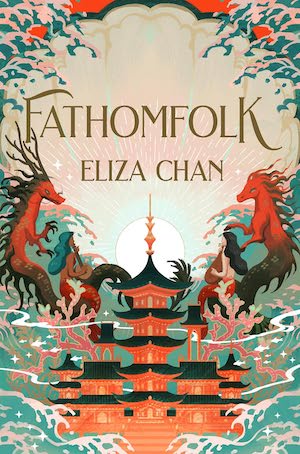

Fathomfolk by Eliza Chan (2024)

Forced from their traditional homelands by human-caused climate change, Fathomfolk are grudgingly granted refuge by those same humans. Relegated to second-class status, Fathomfolk are a valuable but despised underclass. Half-siren Mira has spent her career proving herself a loyal, hard-working guard. She is eventually the first Fathomfolk promoted to captaincy of the border guard. Too bad for Mira that the job largely involves keeping her fellow Fathomfolk in line.

Mira’s sister-in-law Nami cares nothing for incremental social progress. Nami believes in deeds not words! Nami believes in revolution, not evolution! Nami also believes that hunky revolutionary Firth is far too handsome to be as evil as his actions suggest he is. Nami means well. Too bad for everyone near Nami.

Many will suffer for Nami’s belief in the redeeming effect of Firth’s irresistible cheekbones. Not Nami herself. Nami has the most annoying ability to convince those around her to give Nami second chances. This might make Nami a greater threat to the public good than Firth.

Idealists and their selfless drive to change less-than-perfect societies have often transformed such societies… though not always in positive ways. Not only that; their example has inspired authors to pen compelling stories. Idealists abound in SFF. I may have missed some of your favorites. If so, feel free to remind me of them in comments.

Did someone called James Holden? ;-)

Arguably, Holden, in the end, succeeded.

Now, if you had said Winston Duarte….

In a really weird way, Bug Jack Barron (Spinrad), where the villain seems to genuinely think that he is out to improve the world by providing immortality to the rich and powerful. He is brought low, and rightly so.

I think Spider Robinson’s Telempath might fit here, but I’m not going to re-read it to make sure.

“Telempath” has several misguided idealists, including the protagonist, but the scientist who discovers that a universal virus is suppressing human sense of smell, and who decides to broadcast a cure, ought to qualify – with the story starting several years after the catastrophe.

Pournelle’s CoDominium was an admittedly terrible government. It was just the best alternative to nuclear war.

But the Mercenary is not about John Grant, its about John Christian Falkenberg, the eponymous Mercenary, who is an agent of Grant – a politician who appears but briefly. Falkenberg has no love for the CoDominium, nor do his Marines.

I must wonder if the author of this piece actually read The Mercenary?

1977’s The Mercenary, the one whose cover is shown above, is a fix-up of three works: 1971’s Peace With Honor, 1972’s The Mercenary, and 1972’s Sword and Sceptre. Peace With Honor, the first third, is the source of the events I mentioned. Are you by any chance confusing the 1977 fix-up novel The Mercenary with the 1972 novelette of the same title and author?

Unfortunately, I don’t seem to be able to post links here but if you go to the Baen site, select The Best of Jerry Pournelle, click on the sample, Peace With Honor is the final preview. If you go to Pournelle’s ISFDB entry, the novel The Mercenary can be found below West of Honor and above Silent Leges.

@Dan_G: I must wonder whether you actually read the article; Mr Nicholl does not state or imply that Grant is the Mercenary in question; he describes the “ideals” of the parties that formed the CoDominion, which are those of Grant, and that it ultimately fails. Which is what the article is about.

And here is James’s full review of the novel.

The people in David R. Bunch’s Moderan, the ones who replaced as much of their bodies as they could with metal and plastic and did the same thing to the surface of the Earth, with the addition of fortresses from which they could while away their endless days with endless warfare — they did seem positively idealistic about their endeavor. Not merely trying to survive in a poisoned and dying world, but ringing in a new and superior era, forever and evermore. Even though the careful reader may occasionally detect something almost resembling doubt.

The Dispossessed, anyone? To my mind that’s one of the most noteworthy examples of this theme: the socialist idealists run away from the stratified, capitalistic planet to set up a just society that, despite its charms, ends up tending to squelch individuality and talent. Because the children of thoughtful revolutionaries are merely maintaining the status quo.

Good one! That was my reaction on a recent reread; I get the impression Le Guin was suspicious of any doctrine-driven approach to a problem of any size.

Rebecca’s comment brings to mind John Barnes’s “Thousand Cultures” books, beginning with Through a Million Open Doors. That book has someone from a very arts-oriented culture looking, with prejudice, at a culture devoted to a ~utilitarian economic theory that requires obedience as much as thought (we’re told in the course of the book that there are certain ideas that can’t be discussed because it’s known they’ll break the theory). Subsequent books rip a new one for several specialized societies (the only kind of colony that went out from Earth), including the narrator’s own; we’re left with the guess that seeding a world to build a seen-as-ideal past culture (that we don’t fully understand from centuries or millennia in the future) will be a failure — perhaps not as spectacularly as in one of the books, but inevitably.

may the saints preserve us all from the true believers.